The dead in Ancient Greece would often be buried with two ‘obols’, or copper coins, over their closed eyes as part of the funeral rites. The idea was that the coins would pay the fare demanded by Charon, the ferryman to the afterlife.

With just over a minute of Eddie Jones’ post-match press conference remaining after a narrow Wallaby defeat at ‘the Glasshouse’ in Dunedin, the atmosphere suddenly came alive and it sounded like the penny had very much begun to drop with Australia’s head coach.

Jones had swatted away every media delivery with a straight bat, until he began to articulate a new strategy for the national team:

“That’s how we want to play [with ball in hand]. You look at our team, we are a running team.

“We have got big men with the ability to change direction in small spaces, and we want to use that.

“Running, running, running – we need to have a strong running game, and then we have – obviously – good half-backs and good 10s who can shift the ball away when we need to.

“Last week [in Melbourne] was the highest running game I’ve certainly seen, for about 30 years.”

Jones’ Wallabies still have a long, long road to travel in only a few weeks before they face the Georgians on 9th September.

It was as if the coins had suddenly been removed from the eyes of the Wallabies head coach, and Jones realised at long last that possession rugby is far from dead after all. The record, perhaps involuntarily, jammed around the word ‘running’, and the needle refused to move anywhere else for a few priceless moments.

Ireland won the Six Nations Grand Slam by building an average of 107 rucks per game, 35 more than their nearest rivals France. New Zealand won the recently-concluded Rugby Championship by setting an average of 104 per game, 27 more than second-placed South Africa. In the URC, the side which built the most rucks in regular-season play (Munster, with an average of 101 per game) beat the Stormers, who set the least (57) in the final. Right now, the possession game is riding the zeitgeist ahead of kicking and defence.

Now it looks like Jones is making a U-turn, away from his avowed three-and-out policy. The change of heart may have come just in the nick of time. With Fiji seeing off Japan impressively in Tokyo at the weekend, and Wales ultimately beating England in some comfort, 20-9 in Cardiff, pool C is beginning to hot up.

It would be no surprise if it turns out to be more closely contested than the much-heralded ‘group of death’ – pool B containing world number one side Ireland, world champions South Africa, Scotland and Tonga.

There are upsets waiting to happen, especially with the current scrummaging woes of both Australia and Wales neutralising their traditional advantage over the Fijians, and creating a potential vulnerability Georgia will be well placed to exploit.

Jones’ Wallabies still have a long, long road to travel in only a few weeks before they face the Georgians on 9th September inside Stade de France. The obstacles to building a platform for possession rugby in such a short window were amply illustrated in Dunedin.

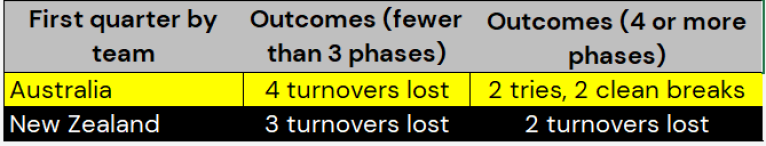

Let’s start by breaking down the Wallaby performance by rucks per quarter:

*Ruck numbers include rucks built under penalty advantage, which count usefully in the possession rugby effect*

*Ruck numbers include rucks built under penalty advantage, which count usefully in the possession rugby effect*

To apply some immediate perspective, Australia set more rucks, and built more sequences of four or more phases in the first 20 minutes at the Forsyth Barr than they did in the whole of the first round of the Rugby Championship versus South Africa at Loftus Versveld (39 rucks, and a single sequence of four or more phases).

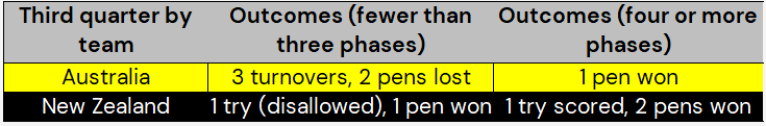

What were the outcomes of these periods of possession?

The real point of interest is the astronomical rise in production once the Wallabies held on to the pill for more than four phases, instead of kicking it away or turning it over at the breakdown early in the phase count. Once they hit four phases, the results were exclusively positive. They kept ball for 11 phases, and the first three minutes of the game, and that set the pattern.

“We have got big men with the ability to change direction in small spaces, and we want to use that,” said Jones – and some of those big men can handle the ball as well.

In this instance, the Wallabies can use Angus Bell at first receiver on the switchback phase after shifting the ball into midfield, without having to tip off the play by moving Carter Gordon’s blond mop back to that side. That represents a massive advantage.

It was typical of the loose-head prop’s influence on attack during the first quarter. After another long break engineered by Mark Nawaqanitawase and Andrew Kellaway, the giant Waratah was on hand to fan the flames in the build-up to Australia’s second try.

Another big run dominates the advantage line and that means lightning-quick ball (LQB) for Tate McDermott at the base, and space for Tom Hooper to finish on the left edge.

Tight forwards such as Bell, and others including Will Skelton, Matt Philip and Nick Frost, are so good on the carry and offload that the Australian game simply has to be designed around them.

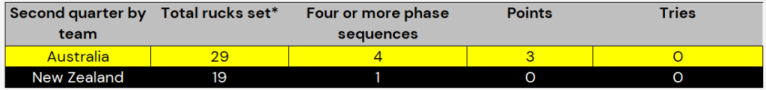

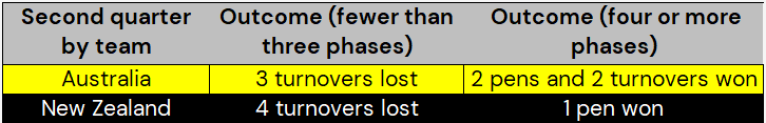

The second quarter hinted at a small but significant decline in Australia’s effectiveness on multi-phase attack.

The Wallabies were twice held up over the goal line in this period, and they were kicking the ball away ineffectually on phases 1-3.

Earlier in the post-match press conference, Jones made the following comments about the collapse of Australia’s multi-phase ambitions in the second half at the Glasshouse.

“The big difference between the two teams tonight – and has been [in previous matches] – is that New Zealand’s work off the ball is better than ours. That is an area we need to improve,” he said.

“We need to develop better habits in that area. When we start to get close, we are going to be a hell of a team.”

In the third quarter, the Wallabies were still kicking the ball away without any obvious purpose on phases one to three.

The big difference was they were giving it back straight away, instead of keeping it when they had the chance.

It is nigh impossible for the man who makes the tackle to successfully pilfer the ball afterwards under the modern refereeing protocols, but Sam Whitelock is able to do both. The twin cleaners (Richie Arnold and Zane Nongorr) are too slow to support the ball-carrier (Tom Hooper), and ineffectual when they finally arrive on the scene. It is an elementary mistake.

At other times, the Wallabies lost their attacking shape completely when they tried to move the ball to an edge.

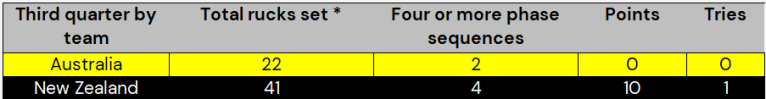

Here are the figures for the third quarter.

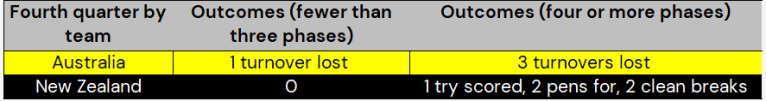

The Wallaby effort at sustaining multi-phase sequences of play with ball in hand finally blew out in the last 20 minutes of the game.

Questions have been raised about replacement scrum-half Nic White kicking the ball away in the latter stages, but he had little choice as the Australian ability to support rucks and realign in attack had disappeared. Ultimately, New Zealand’s dominance in the fourth quarter was as complete as Australia’s control of the first. The Wallabies won the ruck battle 70-37 in the first period, but lost it 90-37 in the second.

Australia were lucky indeed Kiwi fly-half Damian McKenzie had such a nightmare. He had already made five kicking errors, lost ball in contact and in the air, and missed Hooper in the build-up to the Wallabies’ second try before he left the field disconsolately in the 49th minute, to be replaced by Richie Mo’unga.

The solace for Jones and Australia is they are at least now trying to play the game they should have been striving for all along. They are keeping possession for longer periods instead of kicking it away and crossing their fingers – hoping to survive on a beggar’s ration of ball, while making over 240 tackles per game.

It is a positive development. The Wallabies kept the ball for 70 phases (including rucks built under penalty advantage), and that matched their whole-game average for the Rugby Championship in only 40 minutes of play. They moved up a gear into multi-phase attack over four or more phases on nine separate occasions in the first half.

It is the right solution even if it has come three games too late, even if Australia have too few players with the good habits and conditioning values to sustain it for a full 80 minutes. It makes the most of some outstanding ball-playing and ball-carrying in the Wallaby tight-five when at full strength. It embraces the strengths of both Gordon and Quade Cooper in the pivotal play-making position at 10.

It is ‘the Australian way’ and it suits how the game is being refereed. Now, it is a race against time to build that interest in possession rugby quickly enough to overcome the recent improvement shown by Australia’s pool rivals. The pennies may have dropped from the eyes, but the ferryman still has to be paid.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free