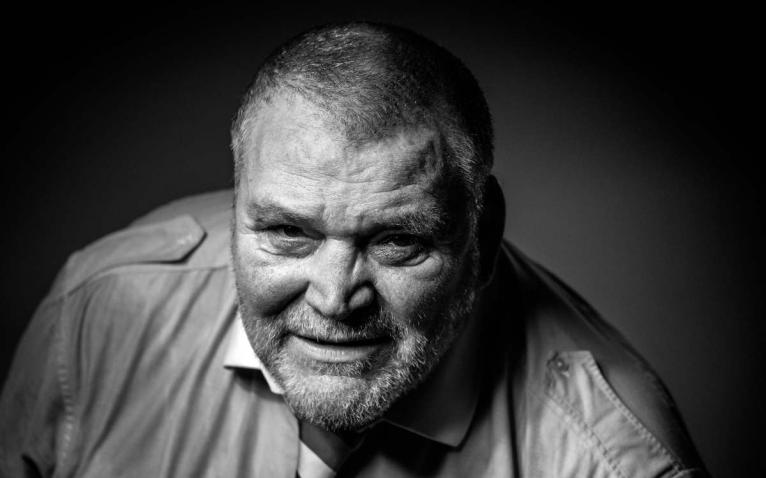

Alain Estève was very much a man of his time. The giant second row – the first French rugby international who stood more than two metres tall – was a yob. On and off the pitch. Convicted of pimping and fraud in recent years, Esteve carried the reputation he had earned as a rugby player in the 1970s onto civvy street. He was a man best avoided.

His death this week at the age of 77 has brought Esteve back into the spotlight. The obituaries have on the whole glossed over his thuggery, making oblique references to his “difficult character” and his “legal setbacks”. Former teammates have laughed off his excesses, although one, Jo Maso, admitted that Esteve was a player “feared by his opponents and also his teammates”.

The pity of it all is that Esteve had talent. First capped by France in 1971, the Beziers second row made twenty appearances for his country in total. It was for his club, however, that Esteve enjoyed his greatest success, winning eight French championship titles with Beziers between 1971 and 1981. He was known as the ‘Beast of Beziers’, not without good reason.

The 1970s was a decade made for a man like Estève. If mindless violence was your thing then the 70s was a golden era. Everyone it seemed was throwing punches and kicking heads, from Springboks to All Blacks to Welshmen. But France had the biggest and baddest headbangers, and most of them played for Beziers.

There was, most infamously, Armand Vaquerin, the prop who won 26 caps, and then killed himself playing Russian Roulette in a Beziers bars in 1993. Estève locked down in the Beziers pack alongside Michel Palmié, whose speciality was the eye gouge. His Test career ended after he was held responsibile for damaging the eye of Racing hooker Armand Clerc in 1978.

Jean-Francois Imbernon, Alain Paco and Elie Cester also had well-earned reputations for, as the great Bill McLaren might have put it, ‘argy-bargy’, but none could match Gerard Cholley – the man they called the ‘Master of Menace’. Against Scotland in the 1977 Five Nations, Cholley knocked down four of his opponents in a manner one writer likened to a “bus conductor proceeding up the aisle taking fares”.

Cholley was a boxer and paratrooper before he became an international rugby player. He was good, a fearsomely strong and technically sound prop, attributes that have been overlooked because of his penchant for punching. In 2006, the doyen of British rugby writers, Stephen Jones, rated Cholley the most frightening French rugby player of all time. When I interviewed Cholley in 2016 I asked him about that accolade. “It’s a compliment!” he exclaimed. “It’s true. In some matches I started on the loose-head and then moved across to the other side if our tight-head was having a problem. I would sort out the problem.”

Alain Estève came from a broken home, one so poor he was eventually put into care, spending ten years of his youth in the supervision of adults who abused him physically and emotionally. Rugby was his way out of his wretched existence and Beziers became his family.

The England and Lions prop of the era, Fran Cotton, described the 6ft 4in Cholley as “a huge nightclub bouncer going to work… you couldn’t take your eyes off him for 80 minutes, he was always up to no good”.

The 1970s was a remarkable decade in sport, reflecting the brasher, edgier and nastier society that emerged from the ‘Swinging Sixties’ where peace and love reigned, at least in popular myth. Rugby had its thugs, motor sport had its playboys in Barry Sheene and James Hunt, cricket had bad boys like Ian Botham and Dennis Lillee, tennis had Connors and McEnroe, snooker had Alex ‘Hurricane’ Higgins, and football had George Best, Frank Worthington and Stan Bowles, to name but three.

The decade was, as far as French rugby was concerned, the heyday for hardmen. There have been a few since – Vincent Moscato, Eric Champ and Olivier Merle in the 1990s spring to mind – but they were more hothead than hardmen. Probably the last fiery Frenchman, in the dirty sense, was Pascal Pape, once described by England’s Simon Shaw as a ‘bit of a schoolyard bully’ who throws the ‘odd cheap shot’.

It was only after he retired in 2015, that Pape revealed his terrible childhood. He had no idea who was his father, only that he was the son of a woman who sold her body to buy drugs. Alain Estève also came from a broken home, one so poor he was eventually put into care, spending ten years of his youth in the supervision of adults who abused him physically and emotionally. Rugby was his way out of his wretched existence and Beziers became his family. As for the rage within Estève, that was visceral, a fury against a world that had been so unkind.

There are two far more significant factors at play between French rugby and the rest of the world; in France, rugby has traditionally been the sport of the working class. The only other major rugby nation of which this is true is Wales.

There are many differences between French rugby players and their British counterparts. ‘Latin temperament’ is often cited, condescendingly, by Anglophone commentators as a way of explaining this difference. Yet, this label isn’t attached to Argentine or Italian players.

There are two far more significant factors at play between French rugby and the rest of the world; in France, rugby has traditionally been the sport of the working class. The only other major rugby nation of which this is true is Wales. But in Wales, players learn to play at school, which is not the case in France.

French schools don’t play competitive sport. If you have a talent for football or rugby or any other sport, you join a club and play on Wednesday afternoons and at the weekend. This system clearly hasn’t held France back over the years, and the professional clubs have excellent pathways in place to nurture young talent as they pass from childhood to adulthood.

What club rugby doesn’t have, however, is the same onus on discipline as schools rugby. When a 17-year-old plays for his school’s 1st or 4th XV he is representing not just the rugby team but also the school. If he receives a red card he has let down both, and often he will be summoned by the head teacher on Monday morning to explain his misconduct. That sense of communal responsibility instils in young players a discipline that a club, however well-intentioned, can’t.

We can state with confidence that there will never be another Alain Estève playing for France. Like Vinyl jumpsuits, instant mash potato and footballers’ perms, he was a product of a decade that subtlety and sophistication forgot.

This is evident in the brawling that is still very much part of amateur rugby in France. Here there are no television cameras to capture thugs at work; so often anything goes. Last season a Fédérale 1 play-off match was the scene of a violent mass brawl, and last month a regional match in Catalan country, in the deep south of France, descended into anarchy with the police required to restore order. Six people were injured and the FFR issued a statement in which they said they were ‘deeply saddened and outraged by these incidents’ and reminded the clubs concerned that rugby is ‘founded on respect, solidarity and loyalty’.

If that message is still struggling to be heard in some quarters of the amateur game in France, at least the national team has cleaned up its act. The Bleus under Fabien Galthie have become one of the most disciplined sides in world rugby. Fortunately we can state with confidence that there will never be another Alain Estève playing for France. Like Vinyl jumpsuits, instant mash potato and footballers’ perms, he was a product of a decade that subtlety and sophistication forgot.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free