Omar Mouneimne has been an entrepreneur. He’s been a photo producer. He’s even been a successful MMA fighter, in the days before the UFC was a blockbuster cash cow. He has made and lost a packet. He has coached some of the world’s greatest club teams under some of their most admired supremos. Recently, he completed his MBA while working at the coalface of the Gallagher Premiership.

Mouneimne is one of the most fascinating figures in English rugby you’ve probably never heard of, yet his influence extends across the sport. The game has taken him from his native South Africa to the cafes of the Champs Elysees, the majesty of Rome, rustic history of Edinburgh, and now, the vibrant streets of Exeter, where he marshals one of the Premiership’s meanest defences.

Why has he been so coveted? How does Mouneimne, at 5ft 7ins tall and with a modest playing background, capture the imagination of British and Irish Lions and Springbok world champions?

To understand his appeal, you have to go back to Johannesburg, where Mouneimne spent his formative years. Born into a Lebanese family, his Muslim father was aggressive, dictatorial and prone to fits of rage when he’d brandish a pistol and point it at his wife and six children.

“He did that frequently, very frequently,” Mouneimne tells RugbyPass. “He’d argue, he’d pull it out, he’d threaten everyone. We’re lucky nothing happened because my mum sometimes tried to take it out of his hand. He became super-religious and tried to control us in a very over-bullish way.

“Home was a mess to study, a mess to rest, you just wanted to get out as quickly as you could.”

The outside world held little sanctuary. Joburg is a gritty place and as a boy, Mouneimne was teased, beaten and even stabbed.

“From day one I was bullied about my name: ‘what a dumb name… that’s a Muslim name, are you Muslim? Are you a devil worshipper?’ I got filled in all the time – all the time.

“My only saving grace was, I was pretty good at sport – without the help of my parents. They never came to watch. I did sport to run away from the craziness of home.

“Over the years of being battered around, I decided whatever the number one form of self-defence in the world is, I want to learn it. I did boxing, muay thai, jiu-jitsu – that culminated in MMA. It turned out I was pretty good. I became someone who could handle themselves and I made that very clear.”

It doesn’t take much reading between the lines to deduce the bullies’ fate.

Handy with his fists or not, money was non-existent. Sick of being told he couldn’t do the things his friends enjoyed, Mouneimne pretended to be older than he was to get a job in a photo shop, similar to Boots. That lit a spark for enterprise which still burns bright. When he grew up and moved to Cape Town, he made his name flipping toiling businesses.

I literally had to get down and dirty and make money however I could. You can’t imagine how much court can cost you.

“I had video stores or restaurants I turned around and sold for profit. I got the turnover up, got them vibrant again and then moved them on.

“My first deal was a video store right on the beach. We cleaned it up, put the stock in a different way, bright lights, then boom, it flew, dude. Then a Nandos opened next door and it really flew. We sold it on and made money.”

As his wealth built, Mouneimne’s reputation as a seriously tough MMA fighter grew.

“I travelled the world, made documentaries, had fights with 10,000 people, paid for cages, rings, ring girls, and unfortunately there was just no money in it. I spent my life savings trying to grow MMA in South Africa.

“Look at it now, you can earn a living fighting in the USA quite easily. I missed the pro era. But I never regret it, I loved it like crazy, trained with the best guys.”

Mouneimne was never extravagant, but he enjoyed the trappings of his success. There were fast cars, bikes and gadgets; riches beyond anything he could have imagined in that turbulent Johannesburg home. Then, it all came crashing down.

He was “screwed on an agreement” by business partners. The possessions he’d bought were pawned to pay hospital bills for the birth of his son and Mouneimne’s fight went from the octagon to the courtroom.

“I literally had to get down and dirty and make money however I could. You can’t imagine how much court can cost you. I had savings and used them thinking I was going to win. I only won years and years later and didn’t win all my money back.”

It was around this time Mouneimne was flicking through television channels when he stumbled across Jake White putting the Springboks through a breakdown drill. This was his eureka moment, an epiphany which led to Rassie Erasmus, the Stormers, and the rest of his life.

“I thought, ‘that’s pretty interesting, I wouldn’t do that’. I was still playing club rugby and getting away with a lot for my size, because I could use my body pound for pound.

“I called some coach mates and told them to bring some players. I swear on my life, my kids’ lives, my mate Darren Viljoen stood there and said, ‘oh my god, you’re going to change rugby – you have to show these drills to somebody’.

“I ended up showing it to the guys at Western Province in 2002 and they gave me a miss. The sevens team were looking for an edge in physicality and I did a demo for coach Paul Treu who said, ‘this is what we want, you’re in’. We did extremely well.

“Then Rassie came knocking and asked me to give him the ‘why’. I gave him the why. He said, ‘sounds amazing, put your money where your mouth is, come outside and show me’. I showed him and he just said, ‘stop talking, you’re in, how much do you want?’ That was cool. I haven’t told many people that story.”

Erasmus and Mouneimne would work together for several years. The MMA grappler learned the art of attack, defence and set-piece from the Springbok giant and his lieutenant, Jacques Nienaber. A rich apprenticeship culminated in the 2010 Super Rugby final.

The attack likes to come up with new things to terrorise the defence; I like to come up with things to terrorise them.

“Rassie is meticulous,” Mouneimne says. “He’d get everyone together and say, ‘we’re going to work on the 20 best ways to place a ball’. He wouldn’t sleep until he perfected these things.

“How he put together the jigsaw of, this is how many points we need from this block, historically this is how you qualify, this is the style of play which has won the most. It was phenomenal. I’ve kept that culture of trying to stay on the edge.”

Mouneimne has travelled the rugby globe since, working with eight clubs and the Italian national side. He has made himself a defensive guru and his teams consistently harder to beat. His Sharks side had the best defence in Super Rugby. His Bristol squad posted top-two statistics without the ball despite their notorious abandon with it. He has been in Premiership semi-finals, won Challenge Cups with Stade Francais and the Bears and worked for Gonzalo Quesada, Nick Mallett, Pat Lam and Alan Solomons.

“Rugby players back when I started were not functionally conditioned,” he goes on. “Their ability to power endurance and body position just weren’t there. Wrestlers, grapplers, that’s what they have. That’s what I gave them.

“I took the rugby league style of upstairs hits, double hits, grappling, choke tackling. Les Kiss brought in choke tackling but I used to call it slow poison.

“My system has evolved, but all the time I’ve tried to coach a highly energetic, highly explosive, decision-making, intelligent defence. You’re brutal but you’re reading plays, making big decisions. The attack likes to come up with new things to terrorise the defence; I like to come up with things to terrorise them. It’s a lovely cat and mouse game.”

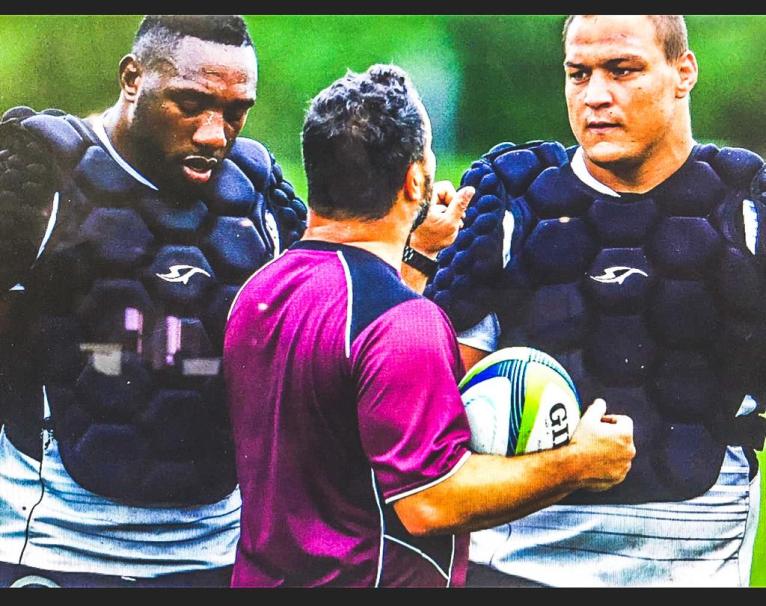

There’s bravery in the blitz, no question, but the snarl is underpinned by exhaustive detail. Simply blasting players with the drill-sergeant treatment will never work. Exeter have been transformed this summer with so many heroes and so much experience heading through the exit door and Mouneimne spent the long pre-season honing Baxter’s new tyros. The first steps in what the club believe could be a new Devonian dynasty.

The results are encouraging. Exeter thrashed last year’s finalists, Saracens and Sale, with a combined score of 108-10 and sit third behind the big two. They have conceded the fewest points and third-fewest tries and ended a 13-month wait for an away league win away at Newcastle on Sunday.

“The art form of teaching young bucks to jam, read receivers, be a menace – it’s underestimated how long that takes,” Mouneimne says. “They’ve caught on quickly but we’re not there yet.

“Is it all about bravery? No, because you can be brave and not have the tools and look like a fool. It’s about having the full myriad of tools at your disposal. That takes some doing.

“We could easily go with a medium press, drift off, let everything unfold, but I don’t think that wins championships. When you come to a semi-final, you want a defence that is as intelligent, innovative and intense as the attack we are facing. You can’t just be a passenger waiting for that attack.

“Hopefully when a play-off comes, and that defence is called upon to deliver, it will be on point. They don’t want to take the shortcut.”

The obstacles come thick and fast in this hamster wheel of a season. Just as they have on Mouneimne’s astonishing journey, grinding along the road less travelled, attacking test after test. It’s the love of adversity and challenge which have spurred him to sample so many environments.

Perhaps some of that stems from the horrors of his childhood. The pistol, the violence, the fear. They shaped him, as a father as much as a rugby coach. Mouneimne has four children – the elder two in South Africa with his former partner, the younger pair with him and his wife in England – and for all the pride in his underdog tale, it is not a strife he will accept in his own family.

“My father grew up rough; he got shouted at, his father was a tyrant too. His anger drove him to brandish that gun. He had a lot of his own demons.

“When he realised he was coming to the end of his life he tried to make amends for crazy things he did. He was remorseful. He would call me every few years and say, ‘let’s meet up, I’m sorry’. I forgave him on the phone but unfortunately he passed before I could see him.

“People have been through worse, it’s not the worst thing on Earth. The upside is, it made me want to be the kind of father who was completely there for his kids, a good mentor who loved them and showed them nothing but kindness.”

Omar Mouneimne has been many things. He was a victim and became a fighter. He was penniless and became wealthy. He was a martial artist and turned himself into an elite rugby coach. Most importantly of all, he was a frightened child who became a doting dad.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free